Sétanta and the Setantii

I have recently been revisiting the theory that Sétanta (later Cú Chulainn), a hero and perhaps a deity the Irish myths, was associated with the Iron Age Setantii tribe of northern Britain. Writing in 2CE the Roman geographer, Ptolemy, refers to Portus Setantiorum ‘the Port of the Setantii’, which was located at the mouth of the river Wyre, and also to Seteia, the river Mersey. This suggests the Setantii occupied the lowlands of present-day Cheshire and Lancashire from the Mersey to the Wyre.

The etymology of Setantii is one of much debate. Graham Isaac suggests it is emended from sego ‘strong’ and Andrew Breeze that is corrupted from ‘the Celtic *met “cut, harvest”, as in Welsh medaf “I reap”, Medi “September” (when corn is cut), Middle Irish methel “reaping party”’. Breeze notes these people were not ‘harmless agriculturalists’ and ‘Welsh literature indicates a bloodier sense’. Medel means ‘reaper’ ‘killer, mower down (of enemies in combat)’. The warrior-prince Owain Rheged is referred to by Taliesin as medel galon ‘a reaper of enemies’. Thus Metantii or Setantii is best translated as ‘reapers (of men), cutters down (in battle)’ and Meteia or Seteia as ‘reaper’.

In Celtic and Manx Folklore John Rhys puts forward the theory that Sétanta Beg means ‘the Little Setantian’, which we might translate as ‘reaping one’, and this would certainly fit with his ferocity in battle.

Rhys associates both Sétanta and Seithenin with the lost lands between Ireland and Wales. In Welsh legend Seithenin caused the flooding of the lands of Gwyddno Garanhir (1) when he failed to close the flood gates due to his liason with Mererid, the ‘fountain cup-bearer’, whose waters were loosed. Traditionally this story is associated with Cantre’r Gwaelod, ‘the Bottom Hundred’, ‘the shallows of Cardigan Bay’. Yet this area extended ‘northwards… off the coast of Cheshire and Lancashire, and occupied Morecambe Bay with a dense growth of oak, Scotch fir, alder, birch, and hazel’.

Gwyddno had two ports – Porth Wyddno (Borth) in Wales and ‘Porth Wyddno in the North’, one of Three Chief Ports in The Triads of the Island of Britain, which was likely Portus Setantiorum.

Holder theorises that Sétanta derives from Setantios and he was originally a Celtic god. Is it possible his mythos, the best developed of all the Irish deities, originated from the people who occupied the lost lands off the Lancashire coast and were later known as the Setantii?

Sétanta’s Birth and Boyhood

The stories of Sétanta/Cú Chulainn were written down by medieval Irish scribes during the 12th century in The Book of the Dun Cow and The Book of Leinster and are now firmly embedded in the Irish landscape. He is associated with Ulster, the Ulstermen, and their king, Conchobar.

‘The Birth of Cú Chulainn’ is a story with much mythic depth. Conchobar rules Ireland from Emain Macha. The plain is devastated by a flock of magical birds, ‘nine-score’ ‘each pair… linked by a silver chain’. Conchobar, his daughter and charioteer, Deichtine, and nine other charioteers hunt them. A heavy snow falls and they are forced to seek refuge in a storehouse where they are welcomed to feast by its owner. His wife is in labour and Deichtine helps her give birth to a son. At the same time a mare gives birth to two colts outside. Deichtine nurses the boy and he is given the colts.

Afterwards Conchobar and his company find themselves east of the Bruig (Newgrange) ‘no house, no birds, only their horses and the boy and his colts’. Deichtine takes the boy to Emain Macha and continues to nurse him but, to her heart break, he dies. Afterwards she drinks a ‘tiny creature’ from a copper vessel. That evening the god, Lug, appears to her and tells her she is pregnant by him and must call their son Sétanta. Because she is engaged to Sualtam mac Róich and fears he may suspect she slept with Conchobar she aborts the child, then becomes pregnant by Sualtam and bears a son. He is called Sétanta and thus has both thisworldly and otherworldly fathers – Sualtam and Lug. His dual paternity, like that of Pryderi, son of Pwyll and Arawn in the Welsh myths, marks him as a ‘special son’.

Lug is an Irish deity who is descended from Cian of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the Irish gods, and Eithne, daughter of Balor, one of the monstrous Formorians ‘Undersea Dwellers’. Sétanta’s descent from a human woman on one side and gods and giants on the other goes a long way to explain his superhuman qualities.

As a mere boy he is described as going to play with the others and fending off fifty javelins with his toy shield, stopping fifty hurling balls with his chest, and warding off fifty hurleys with his one hurley.

Sétanta receives the name Cú Chulainn after being attacked by a hound belonging to Culann the smith. He puts an end to it in a grotesque manner. ‘The lad struck his ball with his hurley so that the ball shot down the throat of the hound and carried its insides out through its backside. Then he grabbed two of its legs and smashed it to pieces against a nearby pillar stone’. As recompense to Culann, he offers to be Culann’s hound and guard Muirthemne Plain until a pup has been raised to take his place. From then he is known as Cú Chulainn – the Hound of Culann.

Training with Scáthach

Cú Chulainn trains with the warrior-woman Scáthach ‘the Shadow’ at Dún Scáith ‘The Fortress of Shadows’ on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. From her he learns the arts of war including ‘the apple-feat, the thunder-feat, the blade-feat, the foen-feat, and the spear-feat, the rope-feat, the body-feat, the cat’s feat, the salmon-feat of a chariot-chief, the throw of the staff, the jump over […], the whirl of a brave chariot-chief, the spear of the bellows, the boi of swiftness, the wheel-feat, the othar-feat, the breath-feat, the brud geme, the hero’s whoop, the blow […], the counter-blow, running up a lance and righting the body on its point, the scythe-chariot, and the hero’s twisting round the points of spears’.

Most fearsome is his use of the barbed spear known as the gae bolga: ‘thrown from the fork of the foot; it made a single wound when it entered a man’s body, whereupon it opened into thirty barbs, and it could not be taken from a man’s body without the flesh being cut away around it’.

During this period Cú Chulainn battles against Scáthach’s rival, another warrior-woman called Aife, defeats her, and offers to spare her life but only on the condition that she bears him a son.

The story of Cú Chulainn’s training with Scáthach shows links with Britain and the existence of a tradition where male warriors were trained by warrior women. This is also found in the Welsh myths where Peredur is trained by the Nine Witches of Caer Loyw and it might be suggested that Orddu, the Very Black Witch, of Pennant Gofid, in the North, fulfilled a similar role.

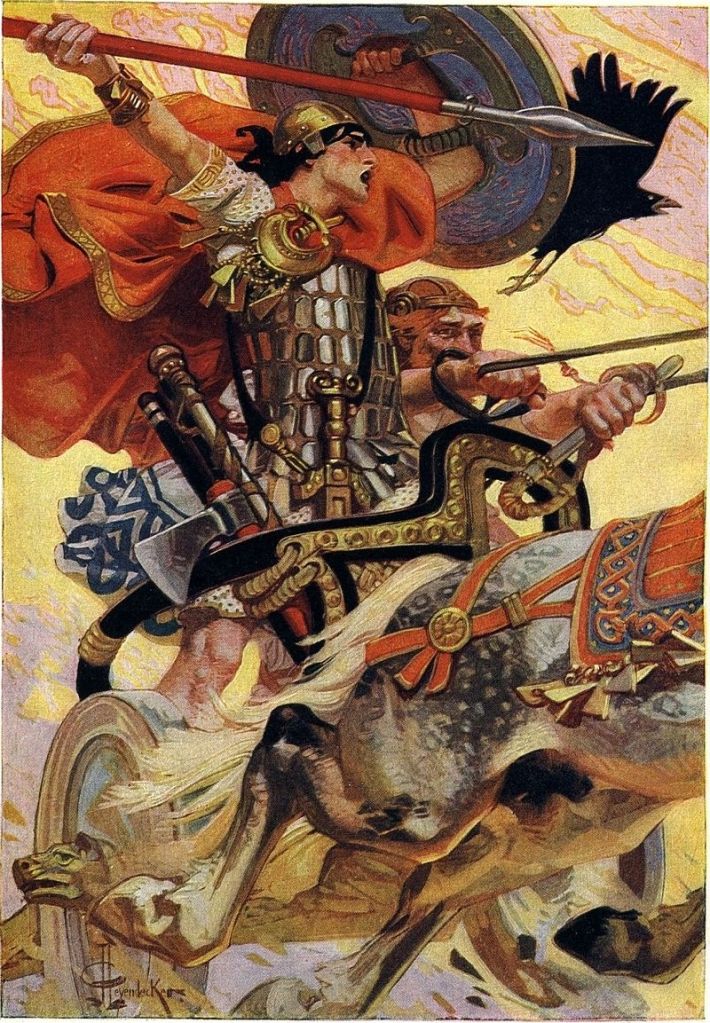

The Battle Rage of Cú Chulainn

After his training Cú Chulainn’s feats are many and his greatest is defending Ulster and the Brown Bull single handedly against the armies of Connacht whilst the Ulstermen are laid up with the Curse of Macha (1). This is recorded in The Tain. After putting them off by magic, picking them off with guerilla tactics and fighting against them in single combat he defeats them in three great massacres.

Here we witness his ability to cause incredible violence. With ‘his scythed chariot that glittered with iron tangs, blades, hooks, hard prongs and brutal spikes, barbs and sharp nails on every shaft, strut, strap and truss’ he drives into the ranks ‘three times encircling them with great ramparts of their own corpses piled sole to sole and headless neck to headless neck’, slaying ‘seven-score and ten kings’.

When he fights, Cú Chulainn is taken over by a battle rage known as his ‘warp spasm’ or ‘torque’. Its vivid descriptions, no doubt a delight to storytellers, driven to greater exaggerations, are worth citing.

‘The first Torque seized Cú Chulainn and turned him into a contorted thing, unrecognisably horrible and grotesque. Every slab and every sinew of him, joint and muscle, shuddered from head to foot like a tree in a storm or a reed in a stream. His body revolved furiously inside his skin. His feet and his shins and his knees jumped to the back; his heels and his calves and his hams to the front. The bunched sinews of his calves jumped to the front of his shins, bulging with knots the size of a warrior’s clenched fist. The ropes of his neck rippled from ear to nape in an immense, monstrous, incalculable knobs, each as big as the head of a month-old child.

Then he made a red cauldron of his face and features: he sucked one of his eyes so deep into his head that a wild crane would find it difficult to plumb the depths of his skull to drag that eye back to its socket; the other popped out on to his cheek. His mouth became a terrifying, twisted grin. His cheek peeled back from his jaws so you could see his lungs and liver flapping in his throat… The hero’s light sprang from his forehead… thick, steady, strong as the mast of a tall ship was the straight spout of dark blood that rose up from the fount of his skull to dissolve in an otherworldly mist…’

In his battle fury Cú Chulainn is described as warped and monstrous and these transformations may derive from his Formorian heritage. This is hinted at in a further passage: ‘Cú Chulainn torqued himself a hundredfold. He swelled and bellied like a bladder full of breath until he arched up over Fer Diad like a monstrously distorted rainbow, tall and horrible as a Formorian giant or a deep-sea merman’.

He also displays the ability to call up otherworldly spirits. His ‘roar of a hundred warriors’ is ‘echoed by the goblins and ghouls and sprites of the glen and the fiends of the air, for their howls would resound before him, above him, and around him any time he shed the blood of warriors and heroes’. ‘The clouds that boiled above him in his fury glimmered and flickered with malignant flares and sultry smoke – the torches of the Badb.’ This puts us in mind of the Scream over Annwn.

Even when he displays his ‘true beauty’ he is otherworldly with his hair in three layers, dark, blood-red and yellow, ‘four dimples in each cheek – yellow, green, blue and purple. Seven brilliant gems gleamed in each regal eye. Each foot had seven toes and each hand seven fingers, the nails or claws or talons of each with the grip of a hawk or griffin… He held nine human heads in one hand, ten in the other’.

Sétanta/Cú Chulainn is depicted a monstrous reaper of men and as a hunter of heads. Head-hunting was common amongst the Celtic peoples, particularly the Setantii, which is evidenced by the large number of severed heads ritually buried across their territories. It has been noted, whilst there is an absence of chariot burials in Ireland, there are many in northern Britain. So there is, at least, an argument that this otherworldly figure, like a giant or merman, originates from the people who once occupied the drowned lands between Britain and Ireland and may have been a Setantian god or hero.

The Tragedies of Cú Chulainn

Amidst the relentless violence endemic to a warrior culture whose greatest aim was winning everlasting fame through battle prowess we find some moving scenes based around Cú Chulainn’s relationships. When Cú Chulainn is badly wounded during his battle against the armies of Connacht his otherworld father, Lug, appears to fight his battle for three nights and days whilst he heals.

Tragically Cú Chulainn kills his son by Aife because he does not know who he is until he sees his ring. In an equally tragic scene Cú Chulainn faces and kills his foster-brother who was also possibly his lover, Fer Diad, with whom he trained with Scáthach. Their relationship is described in poignant verse:

Two hearts that beat as one,

we were comrades in the woods,

men who shared a bed

and the same deep sleep

after heavy fighting

in strange territories.

Apprentices of Scáthach,

we would ride out together

to explore the dark woods.

After many days of battle with various weapons Cú Chulainn puts an end to Fer Diad with the gae bolga.

His lament is heart wrenching:

Sad is the thing that became

Scáthach’s two brave foster-sons –

I wounded and dripping with gore,

your chariot standing empty.

Sad is the thing that became

Scáthach’s two brave foster-sons –

I leak blood from every pore

and you lie dead forever.

Sad is the thing that became

Scáthach’s two brave foster-sons –

you dead, I bursting with life.

Courage has a brutal core.

It puts me in mind of the lines spoken by Gwyn, our British death-god and gatherer of souls, who is doomed to live on whilst the warriors of Britain perish in ‘The Conversation of Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’ (2), which perhaps speaks of a shared origin to these poems.

Cú Chulainn’s love life also contains tragedy. His main lover is Emer but their relationship is put into jeopardy when Cú Chulainn goes to hunt her one of two magical birds ‘coupled with a red-gold chain’. He shoots but does not kill one. They turn out to be fairy women and, when he falls asleep against a stone, they take revenge by beating him with horsewhips until ‘there is no life left in him’.

He takes to his sick bed for a year and learns the only cure is to help one of them, Fand, to battle against her enemies. They fall in love and sleep together yet she is the wife of the sea-god, Manannan. Cú Chulainn returns to Emer but both are heart-broken. Cú Chulainn wanders the mountains neither sleeping nor drinking (3) until Manannan shakes his cloak between Cú Chulainn and Fand so she is forgotten.

Cú Chulainn’s death is fittingly tragic. His old enemy, Queen Medb of Connacht conspires to kill him with the sons of her enemies. He is tricked into breaking his geis of not eating the meat of his sacred animal, the dog, and by this he is weakened. He is killed by Lugaid, the son of Cú Roí, another otherworldy figure with whom he battles and defeats to win a maiden called Blathnat (4).

With a magical spear destined to kill three ‘kings’, Lugaid kills Láeg, Cú Chulainn’s charioteer, Liath Macha, Cú Chulainn’s horse and finally Cú Chulainn himself. Mortally wounded, Cú Chulainn ties himself to a standing stone so he can die on his feet facing his enemies. They remain afraid of him even after his death, not daring to approach until a raven lands on his shoulder. This symbolises he has been beaten by the only opponent worthy of defeating him, the death goddess, the Morrigan (5).

A Hero of the Setantii?

Here I have provided only glimpses into the rich mythos surrounding Sétanta/Cú Chulainn: his birth and dual paternity, his naming as Culann’s Hound, his training with Scáthach, his feats as a warrior, his love life (which features a number of women and possibly a man), and his death.

As we have seen, these stories are now firmly embedded within the Irish landscape. However, we know that many centuries ago Britain and Ireland were near joined together and that the gods, the Tuatha Dé Danann and the Children of Don, share many similarities. Nodens/Nuada, the king of the gods, was worshipped on the Lancashire coast and his son, Gwyn, might have conversed here with Gwyddno. Lug(us) was the patron god of Carlisle (Luguvalium) further north. If he was venerated here it would make sense his son, Sétanta/Setantios, was also viewed also an important deity or hero.

The evidence suggests there is at least a possibility the stories of Sétanta originated from the lost lands off the coast of Lancashire where gods and giants gave birth to monsters, that this monstrous and beguiling head-reaping hero was one of the deities of the Setantii, the reapers of men.

(1) After Macha raced against the horses of the king of Ulster and won she gave birth and screamed that for five days and four nights any man who heard her would be afflicted by her labour pains. She then died. Her curse was passed on for nine generations. Macha’s name was given to Emain Macha.

(2) I was there when the warriors of Britain were slain

From the east to the north;

I live on, they are in the grave.

I was there when the warriors of Britain were slain

From the east to the south;

I live on, they are dead.

(3) His state resembles geilt/wyllt ‘mad’ or ‘wild’ in the Welsh and Irish myths where we find Suibhne Geilt and Myrddin Wyllt taking on bird transformations and Cynedyr Wyllt ‘nine times wilder than the wildest beast on the mountain’.

(4) ‘The contention of Corroi and Cocholyn’ (Cú Roí and Cú Chulainn) is referred to in the medieval Welsh poem ‘The Death Song of Corroi’ in The Book of Taliesin and the beheading game Cú Chulainn plays with Cú Roí perhaps depicts a conflict with the Head of the Otherworld, here known as Gwyn.

(5) The Morrigan appears earlier in the stories as young prophet then fights against him as an eel, a she-wolf, and a hornless red heifer. After the battle she tricks him into healing her when she appears as a one-eyed hag milking a cow with three teats by drinking from each which heals her three wounds.

SOURCES

Andrew Breeze, ‘Three Celtic Toponyms: Setantii, Blencathra, and Pen-Y-Ghent, Northern History, XLII: 1, (University of Leeds, 2006)

Ciaran Carson (transl.), The Tain, (Penguin, 2008)

Eoin Mac Neill, Varia. I, Eriu, Vol. 11, (Royal Irish Academy 1932)

Greg Hill, (transl.) ‘The Conversation of Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’, https://awenydd.cymru/the-conversation-between-gwyn-ap-nudd-and-gwyddno-garanhir/

Jeffrey Ganz, Early Irish Myths and Sagas, (Penguin, 1981)

John Rhys, Celtic and Manx Folklore: Volume One, (Project Gutenberg, 2017)

Rachel Bromwich (ed), The Triads of the Island of Britain, (University of Wales Press, 2014)

Sioned Davies (transl.), The Mabinogion, (Oxford University Press, 2007)

With thanks to Wikipedia for the images of Cú Chulainn. The photographs of the former site of Portus Setantiorum near the mouth of the river Wyre and the coast from Rossall Point where the remnants of the forest have been seen are my own.