A nun in a small room. A big woman, robed in grey, not only her bulk but her presence fills the space. Every ounce of her being, of her focus, of her concentration, is directed to the page on which she slowly, painstakingly, inscribes flowing letters and illuminates the words with beautiful artworks.

How I envy her slow pace of life. The space she has, inner and outer, for this steady work. For her fulfilment in this golden now of creation and lack of cravings for whatever lies beyond those stony walls.

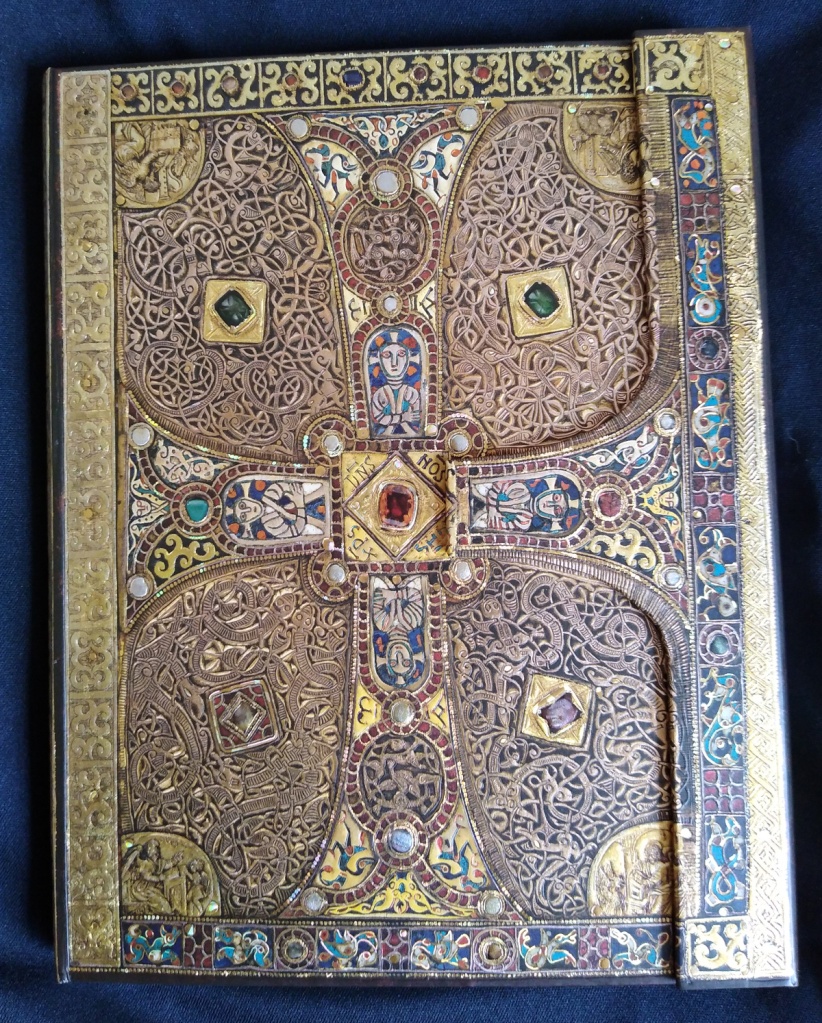

She first appeared to me a few weeks ago and I took this as a signal the time had arrived to start writing in a notebook with a cover based on the Lindau Gospels, which a friend bought for me several years back. I’d never dared write in it for fear of spoiling it as the artwork is so beautiful.

The Lindau Gospels are so named because they were once housed in the Abbey of Lindau in Germany. The lower cover, on which my notebook is based, was produced in 8th century Austria, but its style is that of insular British art. It is predominantly Christian. Around the central topaz are the monograms ‘IHS, XPS, DNS, NOS’ ‘Jesus Christ Our Lord’ and Jesus appears on each of the arms of the cross in a cruciform halo. The four evangelists appear in the plaques in the corners. Yet the spaces between the cross and within the cross are filled with swirling, shapeshifting figures, which morph from serpent to bird to fish to dog and back again, and recall pre-Christian traditions.

Illuminated manuscripts, based on Christian scripture, were produced across Western Europe from 500 to 1600 CE. The phrase derives from the use of gold or silver to illuminate the words and pictures. Many were ‘Books of Hours’ containing devotional prayers said at set times of the day.

I’ve been drawn to such books before. Several years back I visited Stonyhurst College, which was founded by the Jesuits in 1593, with Preston Poets’ Society. Whilst the other poets were geeking out over Shakespeare’s First Folio I was far more fascinated by the prayer books of Mary Queen of Scots and Elizabeth of York one of which, if I recall rightly, was illuminated by lapis lazuli.

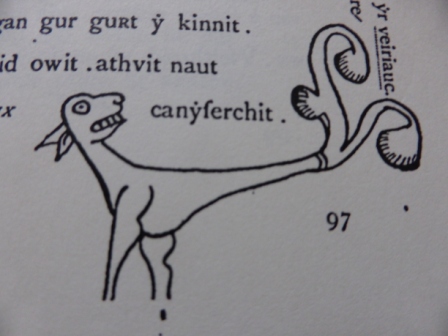

And, of course, many of the medieval Welsh manuscripts which contain the myths of my gods were illustrated by their scribes, including The Black Book of Carmarthen where we find ‘The Conversation of Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’ with a cheeky portrait of Gwyn’s dog, Dormach.

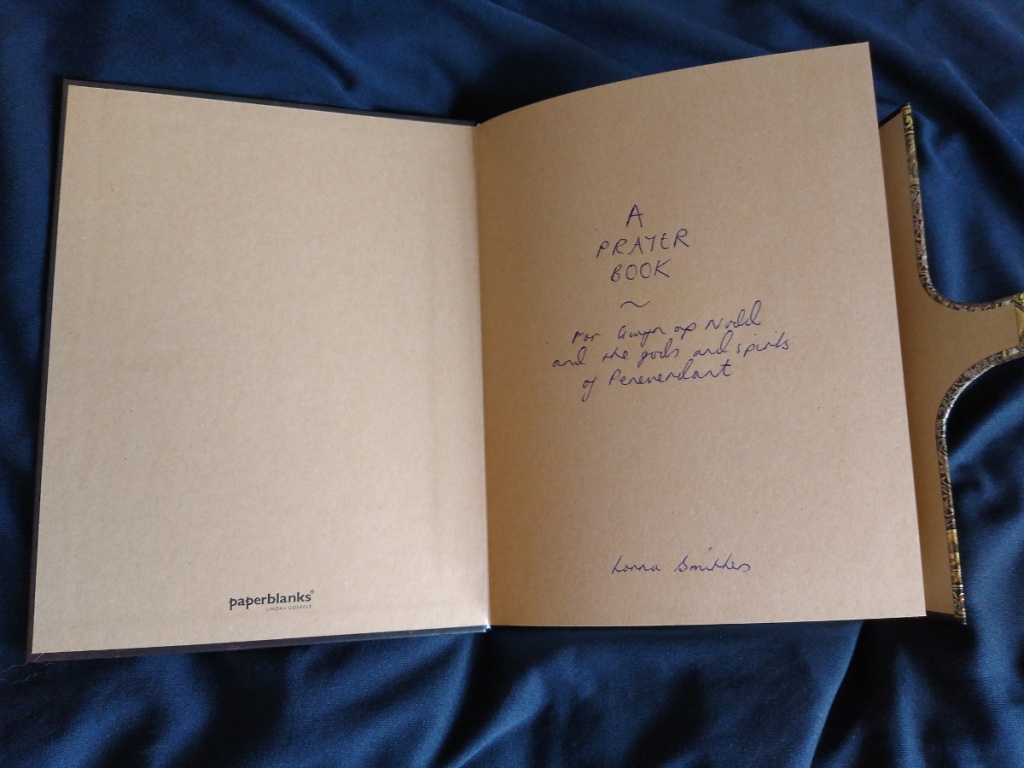

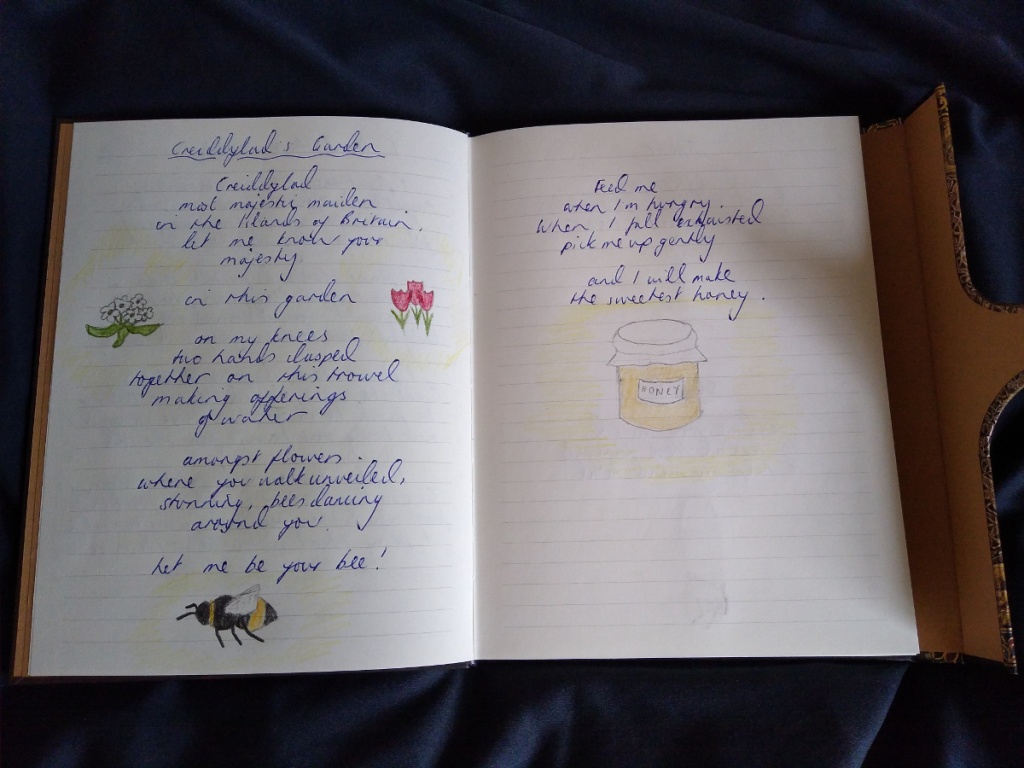

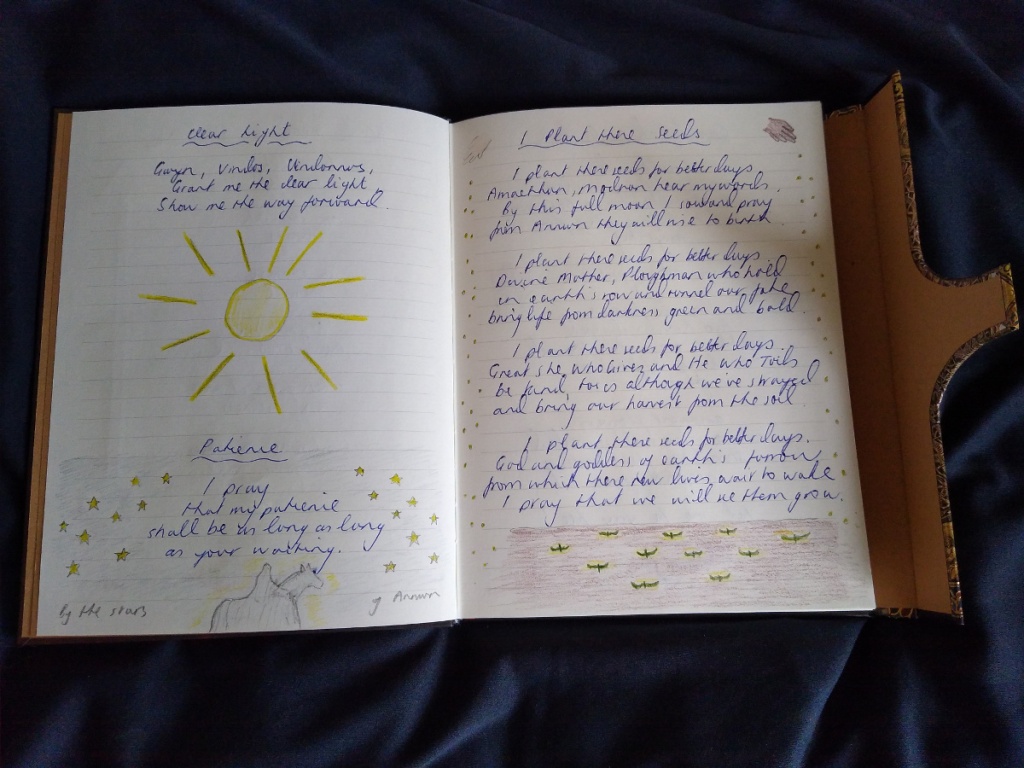

The childlike nature of the drawings in the old Welsh texts and the way the seething mass of pre-Christian imagery unsettles the golden veneer of the Lindau Gospels gave me the confidence and the feeling of rightness to open the notebook, to begin writing. To dedicate it to ‘Gwyn ap Nudd and the gods and spirits of Peneverdant’ and to begin penning within my first prayers and illustrations.

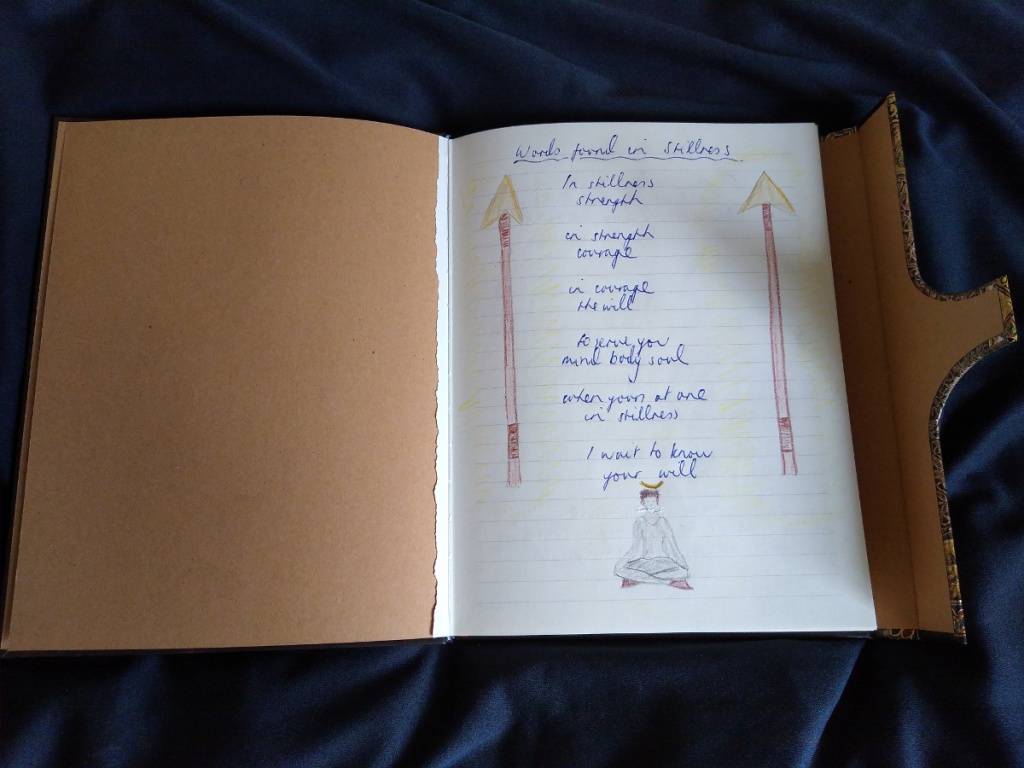

I am now using it as a space in which my re-emerging monastic leanings can combine with my relationship with the Annuvian gods. Where my prayers and pictures are not illuminated by gold but by the golden light of the Otherworld.

Lovely! Good luck with your re-emerging monastic leanings! I found that working on my early breviaries could be a real artistic endeavour.

How beautiful that you’re reclaiming (if that’s the word) something from the Christian tradition and rededicating it. I’ve found it very meaningful as well when I’m able to do that for Gwyn. 🙂

I am severely envious of you for having that beautiful book.